The Wall Street Journal

by John R. Emshwiller

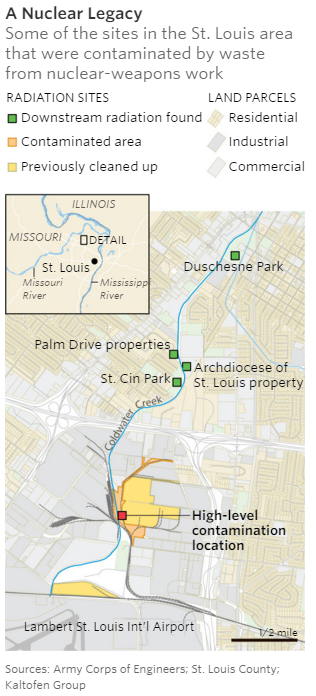

About a mile from homes in Missouri’s St. Louis County lies a radioactive hot spot with contamination levels hundreds of times above federal safety guidelines. But there are no plans to clean it up.

That is because the location, tainted with waste from atomic-weapons work done in local factories decades ago, has been deemed by the federal government to be effectively inaccessible and not a threat.

The site, which runs along and underneath a railroad track, is far off the beaten path and the contamination is covered and anchored in place, said Bruce Munholand of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is removing weapons-related waste at dozens of sites in the St. Louis area.

However, a group of private researchers funded by an environmental activist, including a former senior official of the Clinton administration’s Energy Department, is challenging those assurances.

They say a recent sampling they did suggests contamination from the radioactive hot spot is entering a nearby stream, known as Coldwater Creek, and then traveling downstream into the yards of homes.

The contamination involves thorium, a radioactive material that can increase a person’s risks for certain cancers if it gets inside the body, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

If such a migration is occurring, the hot spot needs to be cleaned up “or it will never stop transporting” the contamination, said one of the private researchers, Marco Kaltofen, who is a research engineer affiliated with Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts.

The Corps has found radioactive contamination in the yards of several homes along Coldwater Creek. Agency officials said they believe the contamination was carried by the creek from sites other than the one the Kaltofen group is concerned about. The Corps said it cleaned up those other sites, which are in a commercial-industrial area upstream from the residential properties.

Though officials have said the levels of residential contamination, which was found 6 inches or more underground, don’t pose immediate health threats, they plan to clean up those locations as well. They have told residents to avoid digging in or otherwise disturbing the soil.

Jenell Wright, who grew up in a Coldwater Creek neighborhood, has been a leader in a citizens’ effort to gather information about cases of cancer and other diseases possibly linked to radiation in the area. The effort has helped push government officials to begin a health assessment.

Though the Kaltofen group hasn’t contacted Ms. Wright about its findings, she said she is concerned about possible continuing sources of contamination scattered around the St. Louis region.

The dispute over the hot spot is part of a larger debate nationally over the radioactive legacy of the nuclear-weapons program. With dozens of locations being cleaned up, one question is how much contamination can safely be left behind. In many of these sites, cleanup issues involve how accessible particular locations are to the public and what future uses might be.

Some of the St. Louis weapons-related waste was stored for a time in piles above ground. Portions of it were eventually dumped in a landfill in the area, where heated arguments continue over what to do with it. Some waste simply fell off trucks and railcars as it was being transported.

Dr. Kaltofen and his fellow researchers—Robert Alvarez, the former Energy Department official, and Lucas Hixson, a nuclear researcher in Michigan—recently did a study regarding possible off-site contamination from that local landfill, known as West Lake. Published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, the study was funded by a St. Louis-area environmental activist.

In doing further work in the area, “we followed a breadcrumb trail of microscopic particles upstream from the residential neighborhoods and found this hot spot,” said Dr. Kaltofen. Sampling found levels of radioactive thorium at up to nearly 11,000 picocuries per gram, some 700 times the federal cleanup standard of 15 picocuries per gram being used by the Corps.

The Corps’ Mr. Munholand said the private research “basically is consistent with our sampling out there” at the location along the railroad line. He said the government’s sampling hasn’t found any evidence the contamination there is getting into the creek.

Microscopic analysis showed the samples from the hot spot, the creek and the affected backyards contained the same radioactive material, said Dr. Kaltofen. He said some of his group’s sampling has found contamination at or near the surface of the ground. If contamination is still getting into Coldwater Creek and being carried into yards during floods, the hot-spot’s level of contamination and proximity to the stream makes it a prime suspect, he argued.

Dr. Kaltofen said he alerted the Corps as well as the Missouri attorney general’s office about his team’s findings.

A spokeswoman for the attorney general said the Corps has deemed the radioactive material at the site as inaccessible. The state has asked for further testing to ensure there isn’t a danger to anyone, she added.

The Corps’ Mr. Munholand said few people go near the site, which is in an industrial area. As part of finishing its cleanup work over the next several years in the St. Louis region the Corps will post warning signs and take necessary steps to ensure the contamination isn’t disturbed.

Dr. Kaltofen said that during visits to the site, which is near the Corps’ local office, he saw people walking in the general area. Some were jogging, walking their dog or carrying a fishing pole, apparently looking to try their luck in the creek, he said.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/radioactive-hot-spot-prompts-researchers-concerns-1461874573